An Installation by Bita Razavi

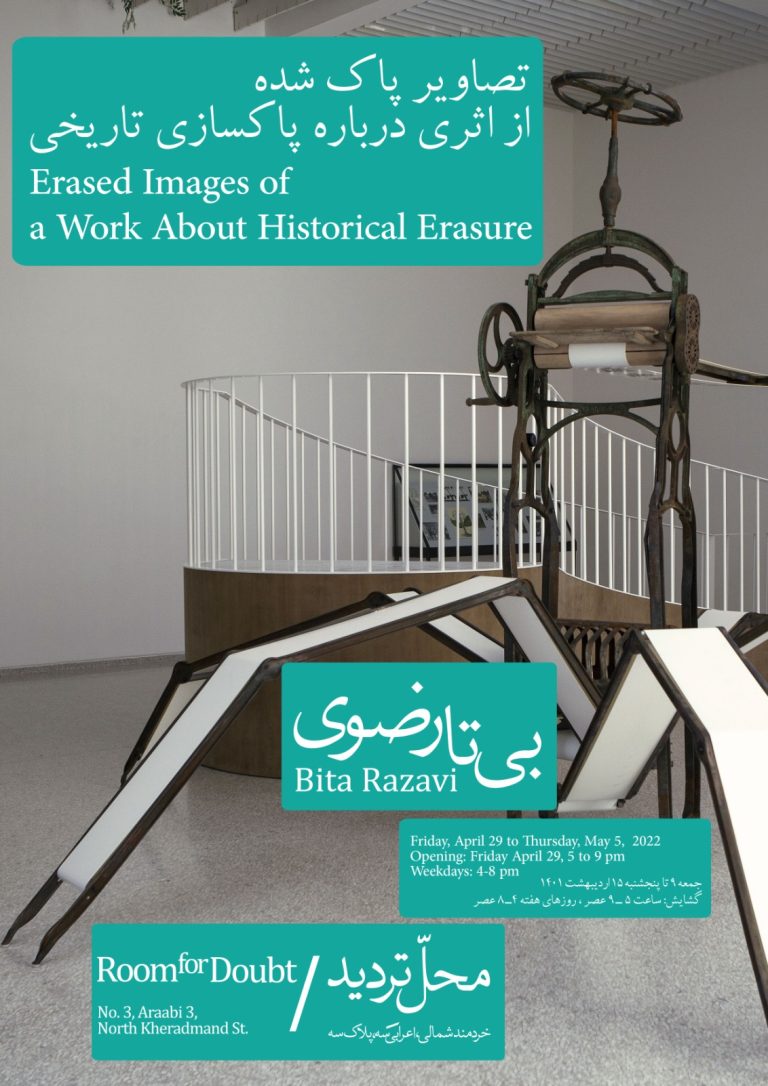

Room for Doubt exhibited Bita Razavi’s installation, “Erased Images of a Work About Historical Erasure.” This presentation dealt with a part of Bita Razavi’s immersive installation which was exhibited last week at the Estonian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. This series of archival photographs depicting destroyed landscapes in colonies that document conditions of colonial extraction of labor and soil due to looting and overexploitation of natural resources was supposed to be part of her exhibition titled Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance displayed in the pavilion. However, the pressure and control of the pavilion’s curator induced the elimination of the photographs in the final show. Instead, some white belts replaced them that formed the lower parts of this expansive installation.

Bita Razavi (1983) is a multidisciplinary artist best known for her auto-fictional practice centered around observations and reflections on a variety of everyday situations. While working as a cleaner in Helsinki, Razavi photographed traces of design in Finnish homes, observing them as manifestations of national identity (2010). She married her schoolmate in her studio at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts to address Finnish immigration policies (2011). She spent four years renovating two houses in Estonia to study Soviet renovation materials throughout years of changing economic and political situations (2019). Razavi was the recipient of Oskar Öflunds Foundation’s grand prize in 2017 and represented Estonia in the 59th Venice Biennale.

Bita Razavi was in Venice when writing this text and by presenting the censored part of her installation in a touring exhibition starting from her homeland, she attempts to shed light on the complications that emerge when European colonial history is narrated solely from the European perspective. and the tendency to veil or highlight certain aspects of it which challenge the notions of integrity and the delusion of liberty in different contexts.

Conceptual Garden: A Stage for Positionality

written by Àngels Miralda

The Designated Entrance

Durational performative intervention

exhibition guard, spectators, three entrances of the pavilion, the guard’s costume

Razavi’s work begins outside of the Rietveld pavilion, where the audience, initially unaware, enters into a system of categorization. The emblematic front door of the pavilion is shut, and a guard dressed in a uniform with herbarium interventions, instructs visitors, one by one, to enter using either of the two side doors. In Dutch colonial architecture, as well as in Estonian manor houses, class divisions are inscribed spatially and the servant class is physically separated and made invisible. The two side entrances of the pavilion offer separate routes to the exhibition, mimicking those designed to separate social classes. One group is given access to an elevated platform, and the other enters the pavilion from the ground. If the Venice Biennale acts as an exclusive zone of privilege for a cultural elite, the performance re-enacts these processes through a spatial and performative intervention. A bureaucratic policing gaze, usually accompanied by underlying racial and class profiling prevails in zones of surveillance, airports, train stations, embassies, and representative national pavilions.

Elevated Platform

Sculptural spatial intervention

marble, teak

The privileged class, selected by the guard, is rewarded with the power of observation from an elevated zone from which the exhibition can be seen, visitors below can be observed, and some works can be manipulated. This platform is situated just over a meter off the ground so that the other audience members symbolically circulate at the feet of the observers. Standing on the balustrade gives a good view of another artwork consisting of an artificial day cycle and a hanging garden. The group on the platform can also enjoy Emilie Rosalie Saal’s botanical drawings produced by the printing press installed in front of the structure. From this position, it is possible to see a combination of elements from an advantageous perspective unavailable to the other viewers. A hidden gate at the base of the platforms allows for the switching of positions to compare the two views of the exhibition.

To reach the tip of the platform illuminated by a spotlight, the visitor has to walk on a floor of marble supported by a ramp made of raw teak. Both products were exploited at the expense of the monumental modification of landscape and destruction of nature in Indonesia. The floor also references the main marble entrance of the Rietveld pavilion built only four years after the independence of the colony. The materiality and design of the platform are heavy historical references that emulate the socio-political conditions which enable some to climb above others.

Kratt

Kinetic sculpture

metal, electric motors, the sound of un-oiled machinery, photographs, and botanical drawings printed on a canvas belt

In front of the elevated platform is a kinetic sculpture evoking a Kratt, a mythological creature from Estonian folklore. Comprising household objects, this machine came to life—the artist asserts—once three drops of blood had been sacrificed to the devil and thereafter performed any task, including wrongdoings, for its owner. The spidery creature moves its mechanical insides to produce images on command for the viewers on the platform while those below can only observe. The upper rollers reproduce Emilie Rosalie Saal’s botanical drawings. These beautiful images emerge from a central printing press that references Andres Saal’s background as a printmaker and the development of modern printing technology which made the colonial worldview tangible for a wider audience through the production of botanical images, maps, and information about the colonies.

This machine represents the possibility of a servant for a servant. Emilie’s practice as an artist relied on the labor of local Indonesian women who worked in her household. Addressing historical erasures and incomplete narratives, the images are placed on the machine’s white belts just as Emilie’s drawings appeared on white backgrounds that detached the plants from colonial contexts. From below, the visitors can barely see the botanical drawings produced by the upper part of the machine, instead, they see images in a rushed loop pressed through rotating rollers resembling the legs of a spider. The legs spin a web of archival images of destroyed landscapes that document conditions of colonial extraction of labor and soil. Among them are archives of the rubber plantation owned by Andres Saal. Despite its offerings, the artist’s Kratt is old and un-oiled—a crooked structure with audible creaks standing on missing legs that, nevertheless, has managed to continue functioning for years.

Allegory of the Cave

Site-specific light installation

artificial light, artificial plants, fans, natural light, shadows of plants, and artificial plants

This artificial light installation only functions fully when observed from the elevated platform. The movement of the sun is mimicked by a staged light source that crosses an invisible hanging garden. Hidden from view, fans imitate wind causing the vines and branches to swing. A full day is completed in an impossibly short ten-minute duration, gliding across the wall, its hues changing before coming to replicate sunset shades. This compressed temporality reflects the abstraction of time in Saal’s drawings and her method of drawing plants in different stages of bloom with various light sources making them uncanny and impossible images.

The play of light and shadow references Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”—a classic reference to perception and knowledge that reinforces the thesis on opacity and positionality played out in the nuances of privilege and illusion. While the viewers on the platform enjoy a perfect view of artificial light and shade, shadows created by natural light are obscured from their view. From the ground floor, viewers can compare this scenographic production with the natural sunlight that enters the modernist windows of the Rietveld pavilion from the opposite corner of the space. This simulation of natural cycles recalls the colonial obsession with recording and categorizing nature through representation rather than developing a connection with the land. Botanical gardens, terrariums, and scientific illustrations capture and offer the tropics in portable, entertaining formats that conveniently deny the simultaneous destruction of landscapes from which they were derived.

References to the blindness of positionality within colonial relations are initiated by the performance of the guard at the entrance and are architecturally reinforced through the class division of the platform. Visitors on the ground can choose to enter the platform after having seen the conditions that support it, and those on the platform can choose to descend and witness the source of what is presented—beautiful botanical offerings which, upon closer viewing, fall flat into the blankness of Saal’s page.